Art Therapy Professor, David Gussak, Finds Art from the Heart Behind Bars

Original article, written by Marina Brown, courtesy of the Tallahassee Democrat.

He claims to have been a “screw-up” in high school; an “idiot” who failed classes and a guy drawn to doing “stupid stuff” — all of it leading to psychiatric facilities, prisons, and death row.

No, he wasn’t incarcerated or ill. David Gussak, Ph.D., ATR-BC., former Chairman of the Department of Art Education and professor in the Graduate Art Therapy Program at Florida State University can walk out of such detention facilities any time he likes. And in again — taking with him graduate interns who are interested in learning the many ways art and art therapy can affect men and women who are mentally ill or enduring long-term incarceration.

Gussak is physically not a big man, but his personality fills his campus office and likely any of the international halls where he lectures a half-dozen times a year. With long, curly hair, sandals, and a bush-hat, he strides around campus smiling, joking, and perhaps mulling over additions to the blog he writes for Psychology Today or for a sixth academic book. His fifth, “Art and Art Therapy with the Imprisoned” will be published this month.

Years ago, the teenage “screw-up” that Gussak remembers himself being was replaced by a passionate academic dynamo, but one who retains an empathy for the people whose inability to express themselves have found voice through art.

“I was born in the Bronx,” he says, “but started college in California. I was paying my way through school and found myself working as a psych tech with gang members.” Gussak says that having seen some of his old friends’ trajectory into prisons and perhaps identifying to a certain extent with these young inmates’ frustrations, he found his own path heading toward a profession which could offer relief to those within the criminal justice system.

One of the art pieces in Dave Gussak’s “Art and Art Therapy with the Imprisoned,” to be published this month.

And art and art therapy could be the key.

Though not a “fine artist” himself, Gussak could early on identify the benefits of creating— with paper, with pen, or when the incarcerated were denied the implements with which to make conventional art — to simply create with whatever was at hand—tissue paper, soap, even food.

Graduating with his Master’s degree in Art Therapy, Gussak began working at a large prison in Vacaville, California at a time when “art therapy” was only beginning to be understood as a therapeutic modality. “Our offices were dreary, dark places… converted cells.”

But his immense energy soon found him presenting workshops and giving talks across the country—and even before receiving his PhD at Emporia State University, he’d become a Board member of the Northern California Art Therapy Association. And he was working with men and women and youth who truly were benefitting from art intervention.

Gussak has gone on to write or edit: Drawing Time; Art Education for Social Justice; Art on Trial; the 900 page Handbook of Art Therapy, and his newest book, Art and Art Therapy with the Imprisoned: Re-Creating Identity.

“In a prison system, people who create have an elevated status,” says Gussak. “They can decorate things; barter their talents for canteen items; design tattoos.” But there is intrinsic value too, he says.

“People in prison have no identity… they are now numbers. With creation, you are in fact, gaining a new sense of self. Some of what “you” is filtered through. And so can the anger and the stress of the incarcerated life.” That is part of the point. Gussak says it’s better to be attacked through art than physically. “Art creation can provide a cathartic outlet for violent impulses.”

In prison, artists can get creative with materials, using melted M&Ms, candy wrappers and cardboard.

But Gussak is a researcher in addition to an art therapist. He says that recidivism is reduced by 80% six months after release from facilities that had art therapy, and by 67% after two years. He says that while creating art pieces, inmates’ defenses are lowered; there is greater socialization; more personal disclosures without anger, and fewer incident reports. And then sometimes, the art that is being made is just plain amazing.

In his office at FSU, Gussak shows a collection of small paintings by John Blasi, a man in his 60s in prison for life for murder—a conviction he refutes. The paintings are blazing with crimsons and golds, turquoise seascapes, and silhouetted palms, much of them reminiscent of the works of Florida’s famous Highwaymen. But there is one difference: many of them were made using the melted-down shells of M & Ms peanut candies —and they smell slightly sweet.“

In a prison,” says Gussak, “everything can be used as a weapon.” Simple brushes and paints, solvents and carving tools, most of the implements of creation are forbidden.” He picks up and admires one of Blasi’s paintings.

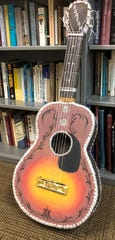

Guitar made with cardboard and “inset” with “carved” tendrils, the bridge is made of candy wrappers.

“I call him the “Candy Man” because after he melted the exterior coatings of the candies, he would add water, blend colors together, paint his landscapes and then coat the surface with furniture polish.” Columba Bush has even acquired one of his pieces.

Blasi has also created a replica of a stone house on footings, complete with an interior spiral staircase—all of it made with cardboard and with gravel picked up a few pebbles at a time from the prison yard.

“Some of the things are ingenious,” says Gussak. He points to what appears to be an elegant guitar propped in a chair. It is light as a feather. Made of cardboard and “inset” with “carved” tendrils, the bridge is made of candy wrappers, the perimeter’s sides are attached front and back by a blanket-stitch of twisted plastic bags and the strings are filament-thin strips of more clear plastic.

Elsewhere, tiny animal sculptures made from soap and delicate roses on paper stems with pink curling petals sit here and there in Gussak’s office — each one suggesting whimsy, or perhaps a hint of romance.

Prison art has found a bit of a cache’ in some circles, says Gussak. “Charles Manson’s paintings sell, John Gacy’s clowns bring in thousands of dollars.” But that kind of sensationalized art is not what interests Gussak. Instead he lingers over the drawings of men held at Guantanamo Bay who since their incarceration there, had never seen the sea. The art from their first view of sky-blue water moves the seasoned art therapist.

“Art doesn’t lie,” he says quietly and wonders out loud at the joy that can be read in the prisoners’ acts of creation.