Dance Professor Premieres “Nepantla” with Primera Generación Dance Collective

Irvin Manuel Gonzalez, an assistant professor of the Florida State University School of Dance, is a founding member of Primera Generación Dance Collective, which recently premiered “Nepantla” in Los Angeles.

Article courtesy of the LA Times | Written by Steven Vargas

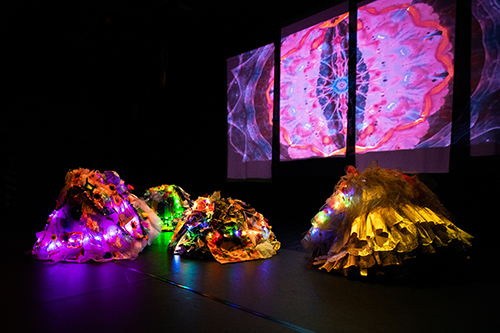

Bodies move together, bathed in memories of Latinidad: a vintage Selena shirt, Mexican snack wrappers and images of Frida Kahlo wrapped together with the tulle of a quinceañera dress. All the while, familiar sounds of Mexican American life play in the background, including the ring of the paletero man driving around the block and the hum of dancing feet.

This is what Primera Generación Dance Collective calls their nepantla, or “in-between.”

“Nepantla” is the L.A.- and Riverside-based collective’s first evening-length performance. Anchored by Alfonso Cervera, Rosa Rodriguez-Frazier, Irvin Manuel Gonzalez and Patricia “Patty” Huerta — the collective initially developed and choreographed the piece as part of an arts residency at a South L.A. dance studio called We Live in Space, but the pandemic interrupted their plans to perform an excerpt in person. The idea evolved into a film for the REDCAT NOW Festival in 2020, and the piece that Gonzalez says was seven years in the making finally premiered onstage at the Odyssey Theatre on June 17.

He calls it a “tough but beautiful process” to get “Nepantla” where it is today.

The four dance artists currently live in different parts of the U.S. and got back together the same week “Nepantla” was scheduled to go up, revisiting movements they’ve rehearsed via Zoom.

“I think there’s a real understanding of what it means for us to be familiar again because it’s been a while that we’ve been in the same space together,” Cervera says.

Huerta says that despite the obstacles of time and location, their sense of familia helped make the process easier, even in front of a live audience.

“Something that we do really well is we sense each other,” she says. “We know exactly in those moments and those minute, millisecond moments what to do and what to react.”

This is just one of many new aspects the collective had to consider as they brought their work from screen to stage. Having the ability to perform “Nepantla” in front of an audience altered how the audience experienced the narrative.

As the dancers go from one section to the next in “Nepantla,” audience members watch as they strip parts of their wardrobe, string them to cable and pull them up at the side of the stage. All changes happen in front of you, and it feels authentic.

“In the film, it’s so easy to make it look like a polished version of it, but something that has always been present in our collective is the revealing process and giving value to that, equally to the actual product itself,” Rodriguez-Frazier says. “The reality is that we’re not polished beings, there’s always an in-between, there’s always a transition. And revealing that is really important to us.”

In each transition, she says that they leave behind a bit of weight from previous sections. As quinceañera dresses sway in the corner and sombreros return in a new portion, the audience sees how everything is intertwined.

“If we were to just sew it all together, what does that reveal for us about who we are as artists and what we’re trying to do for our communities?” Gonzalez asks.

More important, Gonzalez says it speaks to the theme of living in the in-between. The in-between goes deeper than culture, but also the lived experience of Mexican Americans — the joy and sorrow. In addition to displaying love for the community, “Nepantla” shares the harsh realities of immigration, media stereotypes and labor rights.

Gonzalez says the collective was able to “dive deep into really feeling how all those emotions are always taking place, all at once within our community” in an evening-length version of “Nepantla.”

“It became this really beautiful rasquache — a mesh of Latinx futurity with ancestral things,” he says, “and mixing that with activism to see this is what our nepantla looks like. Not everybody is the same way. All of our in-betweens look different.”

The collective invites audience members to participate in connecting to the work and movement to discover their own in-between in the process. It begins in a section titled “Cambio” where the four dancers verbally engage with the audience. They break the fourth wall and narrate their movement. It all leads to a community cypher onstage as people are invited down to dance. It’s a manifestation of joy and celebration of identity and culture.

“Most dancers who are in the audience know what you want, like, ‘I’ll come down the stairs to join you.’” Cervera says. “But there’s also those audience members that have never experienced that perhaps and what are the tasks that are needed to cater to them.”

The collective values the connection they have to the community and their audience. As first-generation Mexican Americans, they want to make the arts accessible and show the next generation that they have space in dance.

“The work is from them and for them,” Rodriguez-Frazier says. “It’s so important that they are able to see themselves within the work and that they feel like they have permission to live in the work.”

She remarked that students would come to see the show and then come back with their parents. She met a mother who shared how connected she was to “Nepantla” even though she thought she wouldn’t understand dance.

Gonzalez explains that at the core of Primera Generación Dance Collective is the goal to share their work that embraces Mexican American culture in any and every way possible. “Nepantla” ventured from various venues as the collective pulled together excerpts from shows they have done at Highways Performance Space, REDCAT and Riverside Trolley Dances. Now as an evening-length show, he hopes to let it continue to travel and connect with people.

“A vision for us too is to share this work, but in a variety of different spaces,” Gonzalez says. “Anything from the Kennedy Center to a park for free.”